Our law firm (along with co-counsel firm Domnick & Shevin, LLP) is currently involved in litigation against the Enterprise car rental company.

Our law firm (along with co-counsel firm Domnick & Shevin, LLP) is currently involved in litigation against the Enterprise car rental company.

In 2008, Enterprise rented a vehicle, in Miami, to a person whose Florida driver’s license was under suspension for failing to appear in court on a number of motor vehicle moving violations. After his credit card was rejected, forcing him to leave the rental agency to obtain cash, he returned with the cash and presented a facially valid (although unlawfully obtained) Texas driver’s license to the rental agent. Enterprise rented him the vehicle.

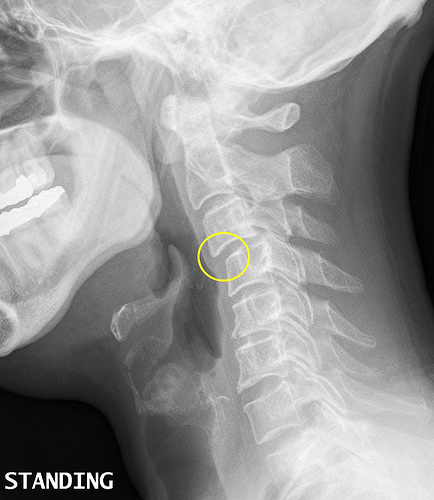

A few days later, the renter caused a high-speed rollover accident in the Enterprise vehicle on I-75 near Gainesville, Florida. Our client, a passenger in the vehicle, was airlifted to Shands Hospital with life-threatening injuries. She remains severely disabled, in great pain, and unable to work.

A quick and inexpensive (less than $1.00) Internet database search, based on name and birth date, performed by the Enterprise agent, would have disclosed the customer’s license suspension and traffic record. However, since the agent was not instructed or authorized by Enterprise to perform such a search, one was not done.

We sued Enterprise on the theory that it negligently entrusted its vehicle to the at-fault driver. Enterprise claims that it did nothing wrong.

What is Enterprise’s primary defense? Florida Statute 322.38(2).

322.38(2) provides as follows – No person shall rent a motor vehicle to another until he or she has inspected the driver’s license of the person to whom the vehicle is to be rented, and compared and verified the signature thereon with the signature of such person written in his or her presence.

Enterprise argues that 322.38(2) is a safe harbor provision providing it with absolute immunity from fault, that despite the ease and nominal cost of determining the prospective customer’s license status and driving record, its only responsibility to the public was to inspect the Texas driver’s license and compare and verify the signature thereon.

The Plaintiff’s (our client) position is that 322.38(2) is not a safe harbor provision extending absolute immunity to Enterprise or any other rental agency. Rather, it is a minimum standard established by the Florida Legislature to create some level of safety for those who travel on the streets and highways of the state, but it is not the only standard that can be considered by judges and juries to determine reasonable conduct under every circumstance.

It is simply not the Legislature’s role to instruct companies how to conduct every aspect of their business. Those business decisions are left to the judgment of the companies, with the understanding, however, that poor decisions or worse can result in serious legal consequences.

Such is the scenario in our case. Enterprise did nothing more than the bare minimum. A judge and jury will now decide if this conduct was reasonable under the circumstances. We do not believe that it was, thus our claim for negligent entrustment. Clearly, Enterprise could have done more.

Continue reading

Florida Rule of Civil Procedure (FRCP) 1.360(a)(1)(A) allows the defendant in a personal injury case to have a qualified expert of its own choosing perform a medical examination on the plaintiff with regard to the injury or injuries in controversy. This type of examination has come to be referred to as a “compulsory medical examination,” or “CME.”

Florida Rule of Civil Procedure (FRCP) 1.360(a)(1)(A) allows the defendant in a personal injury case to have a qualified expert of its own choosing perform a medical examination on the plaintiff with regard to the injury or injuries in controversy. This type of examination has come to be referred to as a “compulsory medical examination,” or “CME.”  Florida Injury Attorney Blawg

Florida Injury Attorney Blawg